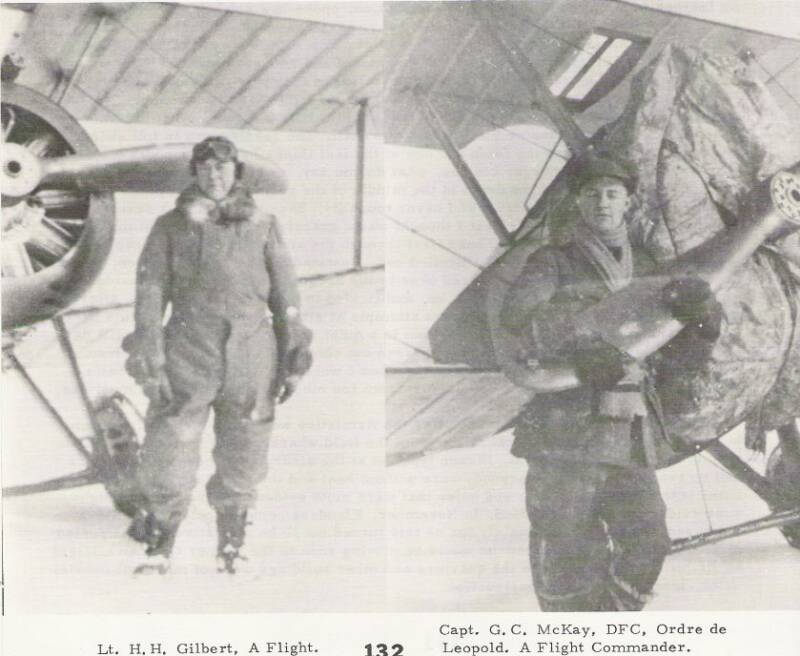

Capt. George C. MacKay, a Canadian and popular A Flight Commander, whose decorations include the D. F. C., Croix de Guerre and the Order of Leopold. This last decortion was awarded by the Belgian King in recognition of MacKay,s part in the action "described above. Which, in addition to Capt. MacKay, were flown by Lts. A. B. Rosevear, H. H. Gilbert and A. S. Chick. Rosevear wrote recently that he believes he was the one who silenced the rear gunner in this fight, after the German had put a burst into his right top wing just above and to the right of his head..

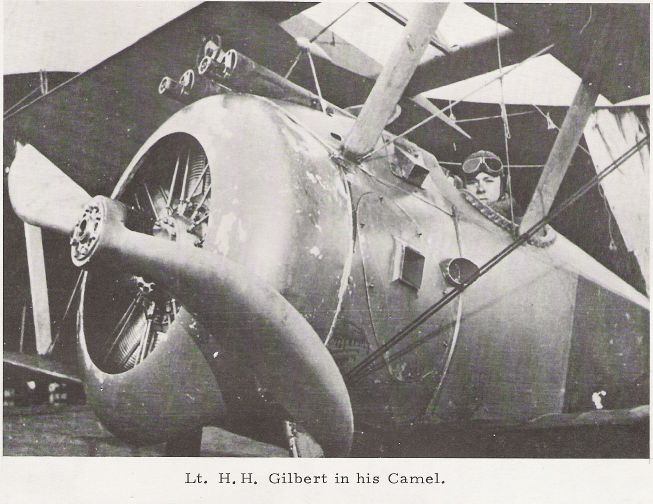

In a letter Posevear describes landing a Camel: "In landing, the throttle was pulled back, then just as the aircraft was about to touch down, the pilot cut the ignition by pressing the 'blip I switch on the control column. The rotary engine continued to revolve by wind pressure, but gave zero power. As soon as the aircraft was rolling on the wheels, the pilot released the pressure on the blip switch, the ignition came on and the pilot taxied on the switch. Three point landings were best for a Camel. Two men usually ran out as the pilot approached the hangar. They held the wings and helped steer the aircraft.

We took off at 9:00 on a morning high offensive patrol and climbed to 19,000 feet in the vicinity of the Belgian city of Ghent where we found and attacked a formation of five Fokker D. VIII's. The German pilots soon broke off the engagement by spinning down and heading east. We returned to patrolling our area and the only notation I made for the remainder of the hour and fifty minutes of our time was, 'Big explosion seen near Ghent.

I was also slated for the afternoon patrol, again an H. O. P., and again up into the very cold levels around 18,000 feet. The open cockpit did not hold heat very well. My only comments for that afternoon's work was, 'N. T. R. (nothing to report) in P. M. ' On the morning of October 31 st, our flight was scheduled for the dawn patrol. After an early breakfast, we "were briefed for a trench bombing and strafing mission in an area of the German lines which was marked on the big map we gathered around in the briefing room. Later, as we walked over to C Flight hangar in the damp morning air, I remembered that my Camel had not yet been fitted with the racks to hold. the four Cooper bombs we were supposed to carry on the mission:--I asked Mackenzie if the sergeant could put a rack on in time for the scheduled take off. One of the other pilots, Holden, was going to be delayed, so Mack told the sergeant to have the rack put on and I was to go with Holden when he took off.

So the rack was fitted to my plane. In the meantime the patrol! took off and was soon lost to sight. I stood by my plane as the bombs were fastened into place and the release arrangement to the cockpit installed and checked. When everything was in order the two of us taxied out and took off, Holden in the lead. We climbed toward the mist shrouded English Channel and then turned for the lines. We hadn't gone very far when the fog began to roll in from the cold waters of the Channel. Pretty soon it got so thick I could no longer see the plane I was flying with. I couldn't see the ground,

in fact I couldn't see anything beyond the limits of my own plane. I knew we couldn't attempt the mission under these conditions so I decided to let down gradually until I could see the ground again. I turned north for the Channel and when I saw it through the mists I turned again in order to keep it on my right. I knew that with the coast in that position I was heading away from the lines.

I flew on for a while and then, just by chance, right underneath me I saw the canal that I knew ran right by our field. I turned immediately and let down even lower so I could see it better and flew along close beside this narrow waterway. A short time later I was abruptly reminded of the first of two things I had forgotten in the excitement and anxiety of getting down safely. The radio mast situated close by our field loomed suddenly out of the fog and I pulled up barely in time to miss it, nosed down on the other side, and there was our field directly in front of me. I landed straight ahead without concern for whatever wind there may have been and ran the wheels along the ground with the tail up, taxiing towards the hangar at a fast clip.As I approached the line, a figure standing near the hangar entrance suddenly turned and ran away from me as fast as he could go. I throttled back, came to a halt and cut the switch. As the Bentley s prop slowed and twitched to a standstill, I climbed out of the cockpit, stepped down onto the wing and jumped to the ground, darned glad to be back on solid earth again. I was just pulling off my helmet when the ground crew sergeant, the one I had seen running away, came back and breathlessly reminded me of the second thing I had forgotten that morning.

Shortly thereafter we began acrobatics. We had to loop it, roll it and spin it. The first time I ever did a whipstall was in an Avro. That' s the damndest sensation in the world! We would pull her up with wide open throttle until she stalled, then we'd cut the engine and she'd drop, nose down and go past the vertical and throw you right out against the belt. It felt like you were being pitched right out of the plane. I remember when we were in Texas we had a cadet killed when he fell out of his plane while doing a loop. He hadn't fasten"ed his safety belt and he attempted a loop. He did get over but he fell in the process. (didn't know him very well, but I remember the incident.) Right after that there was a required lecture for all cadets and we were emphatically told, If the first thing you do when you get in that plane is to fasten your seat belt and see that it stays fastened! 11 We had no shoulder straps, just this seat belt across our waists, quite a wide belt. The Avro also had a very wide belt with a snap on it that would release quickly if you had to get out fast after you had landed. For the next several months we flew the Avro and then the Sopwith Pup. It was a beautiful little plane, so light and easy on the controls, a real pleasure to fly. We spent time learning stunts, practicing formation flying, doing camera gun work, firing live rounds, 'learning about gun stoppages and engaging in aerial fighting practice and simulated forced landings. -- I was making one of these simulated forced landings in an Avro one day and I cut the throttle and started down. As I turned I saw a field that I thought was all right and I kept on going down. Then I saw that there were horses in the field. I was pretty low by then and the horses were in the near end of the field and I would have to land beyond them. Then, as I approached, they started running like hell, away from me right toward the spot I was going to set down. At the far end of the field was a row of trees. Well, I thought I'd better not land, so I gave it the gun and it sputtered and coughed and damn near cut out on me. But right at the crucial point it took hold and I went over the top of the trees. I tell you, that was a grand and glorious feeling!

I got about 45 hours on the Avro and a little over 16 on the Pup during those weeks. One day Captain A. G. Taylor the C. O. of the field, said to me, "Fred, take that Pup up to about 5,000 feet and do a few loops and stunts for me." So I climbed into the plane he had indicated, took off and had gotten to about 500 feet, just over the edge of the field, when the carburetor dropped out onto my legs! Gasoline poured all over my legs and feet and, - of course, there was no motor power at all. The instructors had always told us to try to make a landing straight ahead in emergencies like this, but there was no place to land in that direction, just potholes and rocks. So the only thing I could see to do was to bank her over and try to get back to the field. So around she came, nose down, gliding quietly, heading for the field. There was a hedge along the edge of the field nearest to me, and as I came in my wheels actually brushed its top branches. But the contact merely slowed me down a bit, and I set her down a short distance beyond and bumped to a stop. I was damn near a mile from the hangars, I guess. It was quite a long field, and the C. O. came running out to me and wanted to know what the trouble was. I said, "The trouble is that somebody didn't fasten the carburetor in place!" My puttees were soaked with gasoline and it was a wonder the whole thing didn't ignite. If it had that would have been the end for me. Well, he complimented me and later wrote in my record, "Lt. Sargent is a very keen and competent pilot. " That's why they selected me for a Camel pilot, they told me later'

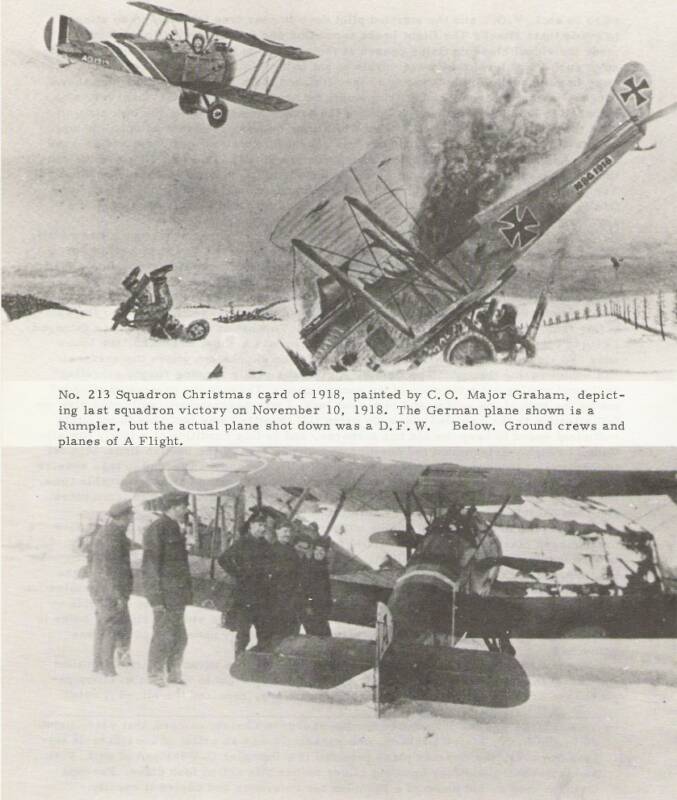

Reproduced from an article in a Cross & Cockade publication 1975

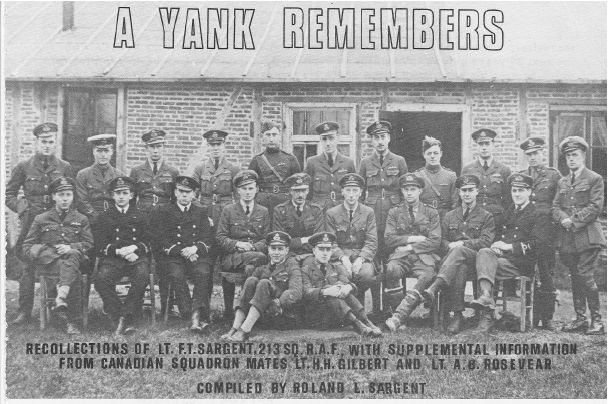

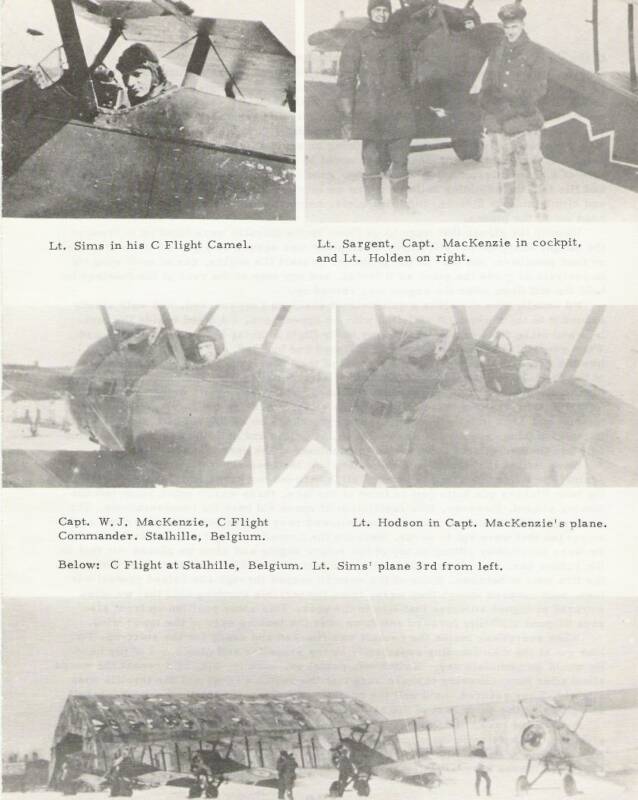

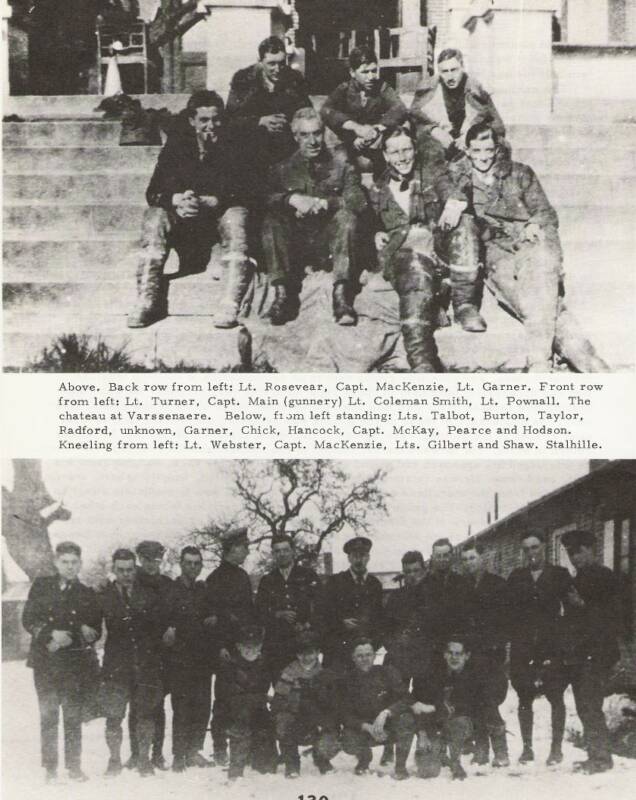

213 Squadron Officers,at Stalhille, Belgium in early 1919 in front of Squadron Operations Room.

Photo courtesy of Department of Defence, Ottawa.

They present a good example of the variety of uniforms within a single squadron. Included are uniforms of the

R. F. C., R. N. A. S. and R. A. F. From left to right, back row: Lts. Holden, Wesley (Rigging Officer), Hodson, Coombs,Not present for the photograph were Capt. MacKenzie, Capt. Maine (Gunnery Officer), Lts. Burton, Gilbert, Phelps, Pownall and Sargent.Frederick T.

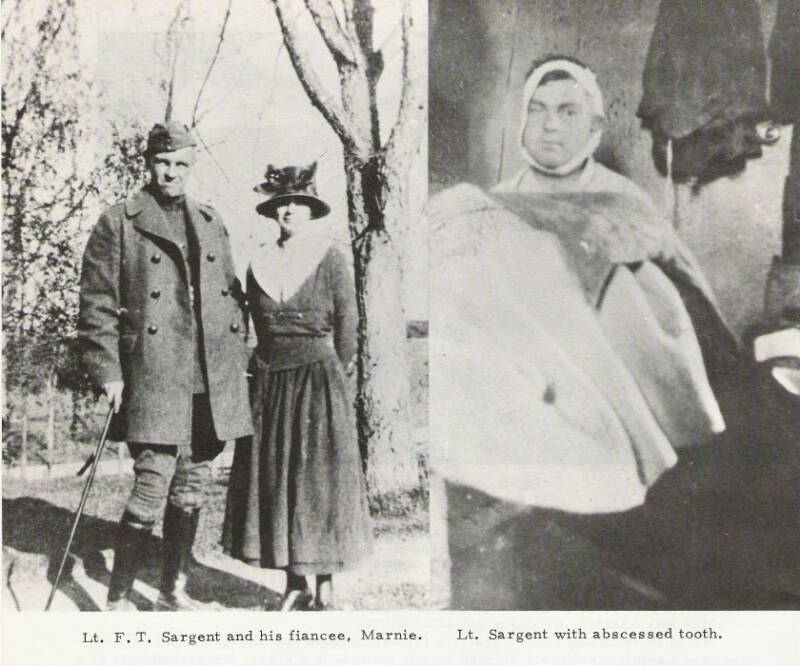

Frederick Sargent was born in Brewer, Maine on December 4, 1891, received his college education at the University of Maine and worked in the Remington Arms' plant in Bridgeport, Connecticut before joining the Royal Flying Corps on October 17, 1917, two months before his 26th birthday. He took his flight training in Canada, Texas and England, and exactly one year and ten days later he reported to 213 Squadron at Bergues, France for combat duty as a Camel pilot. He saw two weeks of aerial warfare before the Armistice, then moved with the squadron to a former German airfield at Stalhille, Belgium for post war duty into the early spring of 1919. After the squadron turned its planes in to Aircraft Park 11 at Ghistelle, Belgium, he and other squadron pilots were sent back to England for a few months in barracks at Sandgate, awaiting transportation home. Eventually they boarded the S.S Megantic and landed in Canada in mid August, with each one heading for his own home and mustering out.

I wrote several months ago to Cross & Cockade regarding permission to reproduce this article Although my contact agreed to raise my request at the forthcoming Committee meeting, I never received a response.. If anyone from Cross & Cockade objects to this article please contact me at my email address. It is an excellent article about a 213 Pilot and I will ensure all the documented accreditation is faithfully reproduced. Brian West, Webmaster

Shortly. thereafter, Fred married the girl he had left behind when he joined the R.F.C. For the next 20 years he was in business in Pennsylvania, and then Coral Gables, Florida which became his permanent home where his two daughters were born and grew up.With the advent of World War II he once again volunteered his services and this time was accepted as a Captain in the U. S. Army Air. Corps. He served with distinction in the Intelligence branch and worked mainly in the Pacific theater in a liaison role with the Navy. After the surrender of Japan he returned home with the rank of major and returned to civilian life. Now, at 83, Fred is active in his church, President of the Retired Peoples Club there and has retained contact with his World War 1 flying days through correspondence with 213 personnel and membership in several organizations, including World War Birds, the Falcons and World War 1 Flyers, a Canadian group.

Fred kept no written records or diary of his days in the R. F. C. and R. A. F. except for his flight log and official service records. As a result, his story presented here, is mostly taken from an interview taped at his home in Coral Gables in April 1973, with further clarification and added information from correspondence with two other former members of 213 Squadron, both of whom presently live in Burlington, Ontario, Canada, Dr. H. H. Gilbert and A. B. Rosevear, Q. C. Because so much of this account is based on memory alone, one has to accept the sometimes eroding effects of 55 intervening years on precise details. In spite of sincere efforts to avoid such detractions, it is possible some discrepancies may be present. If so, perhaps some reader may discern them. However, we trust the account will be accepted solely on the grounds on which it is presented and that is merely the story of personal experiences in the first war in the air as one Yank in the R.AF and two of his Canadian fellow pilots remember them.

ROLAND L. SARGENT October 6, 1974

I first got the idea that I wanted to fly from an article in the Saturday Evening Post which had a picture of a pilot climbing through the clouds in a fighter plane. I decided right then and there that I wanted to fly and that I wanted to be a fighter pilot. That idea became my one great ambition. At the time I was working as an inspector in the breech department of the Remington Arms factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut, making rifles under a contract with the Russian government. This was in 1916, I believe. We weren't in the war at that time, but I decided I was going to get into the service. I went to New York City to the headquarters of the U. S. all through the physical examination. The last doctor said, got a speck of something in your eye ! "Speck in my eye! I thought my eyesight was perfect!" "Well, you know, to tell the truth, he answered, "You should have gone to Boston. You're out of your district here. We couldn't pass you, really, so why don't you go back home and go to Boston for the examination. This is the wrong district for you. " They should have stopped me right at .the beginning, but they didn't. I was so mad that I decided then and there to apply to the Royal Flying Corps. My brother-in-law knew a man who was a friend of Theodore Roosevelt who gave me a letter of introduction to Lord so and so, I forget the gentleman's name. He was in charge of the British Recruiting Mission for the Royal Flying Corps, in New York.

I went to the Recruiting Mission on Fifth Avenue, found my man and gave him the letter. He read it, congratulated me and sent me to 280 Broadway for the required physical examination. I passed it and was all set. They told me to return to my home in Brewer, Maine and wait for a telegram that would tell me when and where to report. A week later I was instructed to report to New York on a certain date to go by train to Toronto, Canada. There were other Americans there in the group and we went together on the same train. We took the oath in Toronto and were taken down into the basement of a hotel where the headquarters was located, and a British officer read the oath of allegiance which was to make us British subjects for the duration of the war and subject to the military law of England. We had to raise our right hands and swear allegiance to King George the Fifth. At that point, October 17, 1917, I became a cadet in the Royal Flying Corps with the rating of third class Air Mechanic. If you didn't make the grade that's what you ended up as and that was your pay. If you made the grade you became an officer. We began our training at the University of Toronto with classes on aircraft engines, machine guns, the theory of flight, navigation and the like. It seems to me that we had to take the machine guns down and reassemble them blindfolded in something like a couple of minutes - on both the Vickers and Lewis types. From Toronto we were sent to Deseronto, Ontario, over near Kingston, where we took military drill, machine gun firing and that sort of thing. After the preliminary ground training we were brought back to Toronto near the end of January, assembled into several squadrons and put on a train that would take us way down to Texas to begin our flight training. On the way down we stopped in some city and paraded through the town. I never saw so many girls. They were in the crowds along the sidewalks and at the windows of buildings, throwing flowers out at us. I guess they were curious because we were the Royal Flying Corps and the American Flying Service wasn't much at that time, it was just beginning to get organized. But we were a going concern and the British uniform was a darn good looking uniform, much better than the American. The American uniform was not made for a Sam Brown belt, it would sag down around their tails. The British tunic was longer and we had a regular lapel coat, a tunic, really. When we eventually got to Texas we were assigned to Taliaferro Field No.2 between Dallas and Fort Worth. There were wooden barracks and a whole row of wooden hangars with concrete floors. I've forgotten how many hangars they had, but there must have been twelve at least. The Headquarters Company and the mess hall were in frame constructed buildings and we were quartered in tents. On February 6, just two days after we arrived, I had my first flight, ever. My Instructor was Lt Moseley and we were to fly the Curtiss JN-4 with a 90-0X motor. Moseley indicated that I was to occupy the front cockpit. We got in, the prop was swung and the engine started. We moved out onto the flat, grassy field, swung around into the wind, and with a surge of sound we rumbled forward, gathering speed over the turf and lifted into the air. It was so smooth. I watched the earth dropping away from us as we climbed steadily. Suddenly the motor began thropp thropp- thropping! Sitting in the front seat the exhaust pipes were right opposite me along either side of the fuselage. Flames began shooting out from the open ends of each pipe. I looked around at Lt. Moseley and to my dismay he looked concerned. He throttled down and we went into a glide. He was headed for a field, but all I could see was a farmhouse and a barn, and it looked like we were headed right for the barn. I remember the queer feeling in my stomach as I realized there was going to be a forced landing. We went in over the top of the barn and came down onto the furrowed surface of the field, landing parallel to the lines of low, earthen ridges, rolling only a short distance before coming to an abrupt halt.

There was another plane circling overhead, flown by one of the other instructors, and he landed nearby. After he and Lt. Moseley discussed the situation I was told to get in this other plane to ride back to the field. At that point I was a little nervous, but I felt better when we got into the air and by the time we had landed back at the main field my uncertainty had disappeared and I was rearing to go again. I got about five hours of dual instruction before they turned me loose. On the day of my solo I went around the landing circuit three or four times with Lt. Moseley, practicing take offs and landings. I had the stick and I couldn't feel him on it - maybe he was, I don't know, but they were pretty good landings. He complimented me and said, "You're ready to solo, taxi over there. I did and he got out of the rear cockpit and stood by the fuselage giving me his last minute instructions. I shoved the throttle ahead and away I went - across the field and up, climbing nicely. As I banked over into my first turn I could see; Moseley, a solitary figure standing on the ground. I wished he was in the plane with me. I went on around, made my turn onto my final approach and came in over the hangers, just floating in, down, down - and I made the most beautiful landing! I was holding the nose right on the horizon as I was letting down. I forgot that I was gliding in. I was just floating in, barely above stalling speed. I touched down and rolled to a stop. Mosely came running toward me yelling, 'Don't go up! Don't go up!" When he got to me he said breathlessly, "How did you do that? Why, you made the most perfect landing I've ever seen for a greenhorn. " I said, "I kept the nose right on the horizon. " The nose right on the horizon? Didn't you know that you were gliding in and you're supposed to keep the nose below the horizon when you're gliding?" Well, I had it throttled back, it just kept floating and by the grace of God it didn't stall out. The next time I began my approach I put the nose down and let her glide instead of holding her right on the horizon. You see what damn fool things you can do when you don't really know what you are doing? You couldn't make too many mistakes in those planes, though. They were fairly stable. As you know, the Jenny was a biplane with quite a wingspan. I think it was darn near forty-five feet. They had a good motor and the mechanics did very well with them. We had to practice simulated forced landings, however, just to be prepared for the real thing. We had to climb up to about 3,000 feet over the field, throttle back, then judge the best power off approach we could achieve for a safe landing, without using the throttle and landing wherever we came down on the field. Of course, if we misjudged and saw we weren't going to make it we had to give it the gun and go up for another try. It was vital practice that saved many a life later on in our flying service. After I had soloed I practiced landings for a while. Then with a camera attached to the side of the fuselage, we were required to flyover certain designated areas and take pictures of the terrain. If we didn't come back with pictures of the right area we didn't pass that phase of our training. After that, it seems to me, a simulated Lewis machine gun, that was in reality a camera loaded with film instead of ammunition, was fixed to the cowlings of our planes and we would take them up for mock combat with another student and take pictures. The idea being to get into a favorable attacking position so that the pictures you took would show your opponent's plane in positions that would have been hits if you had been using real bullets instead of harmless film.

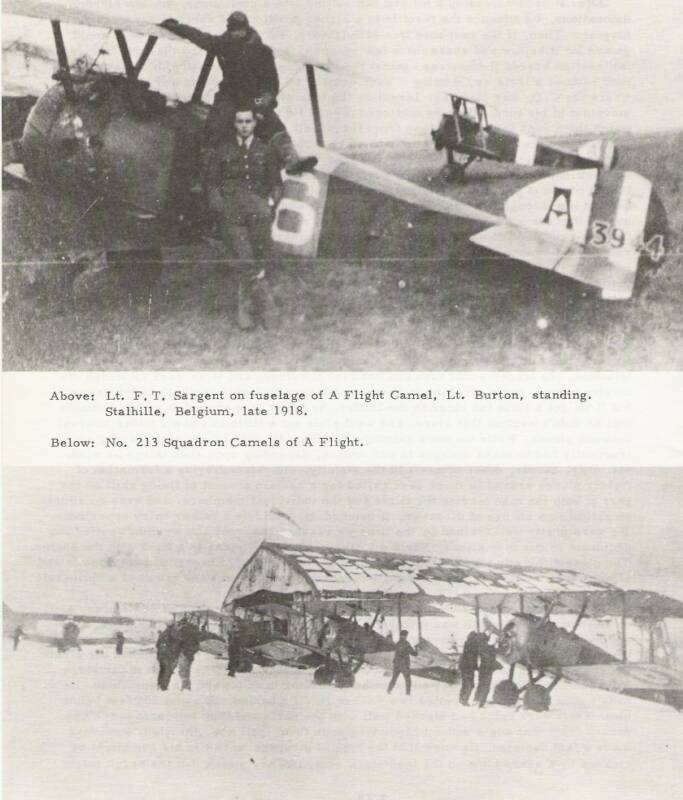

Above: Crash of a Camel near Dover, England that was being ferried to France in the latter part of 1918. Pilot' unknown.

Below: B Flight, No. 213 Squadron, at Bergues, France in late 1918.

We were out on the field at this stage and some of the boys were quite nervous about this requirement. I was sitting there waiting my turn. The C. O. wasn't there but some of the instructors were .lounging around. A student came over to me and said in a low voice so as not to be ..overheat:, "Would you take that plane up and use my name? Ive got my wind up. I can't do it. So I took the plane up I took the pictures and he got the credit.There were quite a few cadets killed during the training there in Texas. There was a Packard ambulance that stood on one side of the field and they called it "Hungry Liz. I It sat there all the time and every time a crash occurred they would run it out and pick them up. Several of the planes caught fire. In one, the student was burned so badly,that just the stub of his nose was left and the rest of his face was frightfully scarred. The only thing that saved his eyesight was the fact that he was wearing his goggles. His engine caught fire in the air, and being in front of him, the flames came back over him. It was a wonder he wasn't burned to a crisp. Usually they were there were no parachutes.

Vernon Castle was instructing at a field not far off at about this time and he was killed in a crash while instructing a student. The usual arrangement was to have the instructor in the rear seat and the student in the front, but Castle reversed this and put his students in the rears.eat. So in this crash he was killed in the front seat, but the student survived. In a gesture of compassion I though deeply grieved at her own loss Mrs. Castle gave the cadet her husband's sports car. During the time I was in Texas I logged about 32 hours solo and 6-1/2 hours dual air time. After we had finished our flight training there in mid-April, we were sent back to Canada to the School of Aerial Gunnery at Hamilton, Ontario with Major J. A.Cunningham as C. O. We didn't have very many planes, and at times we had to use machine guns on the ground to get in our firing practice. We used Curtiss IN -41 there, too. It was there that I logged my only time as "Passenger" 1 hour 45 minutes. I guess I must have gone along just for the ride on that one. Our training at this stage involved work with cameras, tow target firing practicel experience with c. c. gear and gunnery on silhouette targets. This was the end of our training on this side of the Atlantic and an May 14, in a brief ceremony without much fanfare, those of us who had satisfactorily completed all requirements to date were commissioned 2nd Lieutenants in the recently formed Royal Air Force of King George V, presented with the appropriate papers and credentials and shortly were sent to our port of embarkation where we boarded ship, rendezvoused with a convoy and set sail for England for the final phases of our pilot training.

We landed at Liverpool and from there were sent to various training schools in England. I was ordered to 204 T. D. S. (Training Depot Squadron) R. A. F. at Eastchurch on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent. This was on the southeast coast of England, not far from the mouth of the Thames River. At Eastchurch I started on the Avro 504, a two-place machine with rather a long, slender fuselage and a large skid that projected out ahead of the undercarriage wheels. It was a nice plane to fly and had only one fault that we were warned about; when we started our take off run and put the tail up, it had a tendency to swing. If we weren't careful it would ground loop quite easily. You had to use your rudder to hold it in line until you had picked up enough speed to get off the ground. It didn't seem to bother me much, but it did some of the boys and once in a while they! d lose control of it and around she'd go My first flight was on June 24 with my instructor, Captain Cocky, and after an hour and 45 minutes of dual time with him, I soloed the Avro.

Sargent's log book entry for this first flight was: Date: Feb. 6,- 1918. Time: 7:15- 7:25. Pilot: Lt. Moseley. Machine Type: Curtiss IN-4 #C461. Height: 500 Remarks: Joy ride - 1 forced landing.

Of course, I had been very lucky too on that occasion. Usually it was too risky to attempt a turn after losing your engine at a low altitude like that. If it had stalled, it would have been too low for a recovery and that would have been it. When I'd been at Eastchurch about two months, a Major G. L. P. Henderson came in with a two-seater Camel. He had been at the front and had quite a lot of experience. I was in the first group to go up with him, having had a little over eleven hours on the Pup up to that time. When we were in the air in this unusual looking Camel the Major spoke through the tube to me and said,"I'm going to show you how to hold her off so she won't go into a flat spin" They had a tendency to go over from the torque effect of the rotary engine, and once they got on their back, it changed the center of gravity and they seldom could be brought out of that type of spin - it was almost always fatal. The torque in a right hand, turn was very marked and you had to hold her off with opposite bank and rudder to prevent her from going over. Henderson said to, push it over hard, give her hell!. We practiced turns for a while, then he said we would climb up to a higher altitude and he would show me how to spin it. He said, cut your throttle back and hold her straight and level, and just let her stall herself. When she starts to fall, if you want to spin to the right, kick right rudder and pull the stick over into the right hand corner, and she'll spin to the right. And" she spun like hell! Then he said, Now shove the stick forward and neutralize

a great relief from the sadness of the other. The loss of Tommy and his friendship was a blow to me, but there were to be others.your rudder. And she came out of it all right. I got only two hours instruction in that Camel with Major Henderson, but it was a wonderful help in giving me the confidence I needed in learning how to cope with such a tricky and sensitive plane. It sure was a far cry from the reliable and stable Pup. I clearly remember the day of my first solo in the single-seat Camel. I was a little apprehensive because so many had been killed in their first Camel solo. However, such was not to be my fate and I was delighted to go up and come down safely. I was all enthused with my success and was going up the hill to the mess hall for breakfast and met Tommy Kestiton coming down. Tommy was an English lad and had been employed by the Rolls Royce Company in New York before joining up and had gone through training with us all the way from Texas. He was on the way down to the flight line for his first flight alone in the Camel. We stopped for a minute on the path and he asked if I'd had my solo yet. I said, Yes! and he said How1d you like it? 11 . Oh, gee, it was fine, Tommy, I answered. You,ll like it.But he looked dubious. You know, Ive got my wind up, I'm nervous about it. 0h, Tom you won't mind it.I said, They're wonderful. to fly. Just take it easy. We parted. I went on up the path to breakfast and he went down to the line for his appointment with the Camel. Ten minutes later he was dead. Somehow he got into a flat spin and spun right into the ground. He was already dead when they got to him. In the last several months Tom and I had become good friends, so I was asked to be one of the pall bearers at his funeral. One of the saddest things I ever saw happened then. His mother lived in London and she came to Eastchurch for the burial.. She was at the graveside as we were lowering the casket into the grave with ropes. The English casket was mummy shaped, with its broadest part at the shoulders, and as we were letting it down, it got about halfway and got stuck - it wouldn't go any further. It was an awkward moment. We had :to pull it back up again, then slowly let it down a second time. All the while his mother was standing right there. Fortunately it went down all right that time. In accordance with British custom the march to the grave was at a solemn, slow pace, with the band playing the mournful Funeral March. But after the grave side ceremony was over, on the return march from the cemetery, the band launched into some currently popular quick-step music.

Later, after the Armistice, Cpt Taylor assumed command of 213 Squadron at Stalhille, Belgium.

Ground crews on the two rear rows. Front row from left:Lt. Holden, Lt. Talbot, P. N. A. S., Capt. MacKenzie, Lt. Hodson, Lt. F. T. Sargent. Stalhille,Belgium.

Below. Unknown mechanic on left. Lt. F. T. Sargent in cockpit, and Capt. McKay.

One clear, cool morning I had left the mess hall after breakfast and was coming down the hill toward the flight line when I saw two Avro's collide several hundred feet in the air directly over the field. They just seemed to collapse into each other, wings crumpling and pieces falling away. Then from the midst, a burst of flame and the whole, blazing mass careened toward the ground trailing an irregular column of black smoke and tumbling bits of

debris as it fell. It hit the ground with a resounding crash. A wave of nausea hit me. I could see that awful pall against the sky all the way down to the ground.

I made my way down to the field. When I got there I found that the four occupants of the two planes were fellows that I knew very well. I had talked to them a short time"before. Now all four were dead, consumed in that flaming mass on the field. When the C. O. saw me he asked if I knew the men. When I said that I did, he told me to get into a plane right .away and take off, not to wait. When I walked toward the plane I had to push my legs. I wasn't at all anxious to go up at that point. But I got into the plane and went through the process of starting the engine, then taxiing out and taking off, and, to my relief, I felt better as I climbed away. Looking back I could still see the wreckage and the rising plume of smoke, but it didn't seem to bother me as much as it had earlier. I guess it was because I was doing something that took my mind off the tragedy, at least for the moment. They used to say that if you didn't get into the air soon after seeing something like that, chances were good that you wouldn't be able to face the strain and uncertainties of learning to fly. One of the boys killed in that crash was a Canadian and I was appointed to act as his executor. You know, getting all his belongings together, finding out who his next of kin were, and so forth. Come to find out, he had two wives. He'd married a girl in Canada, and then when he came to England he met another girl and he married her! So there was a question as to whom to give the gratuity. Well, they gave it to the first wife. The second wife came down to Eastchurch and tried to claim that she was a legal wife, but it was found that he had been legally married to the first girl in Canada, .so all his things and money went to her. I guess it was because they were just kids and they got overseas, away from the moral restraints of home and normal surroundings, and they just did some crazy things at times. Some of them figured their lives weren't worth a nickel and they might just as well raise some hell for a while. We were all under a strain. At the front there was a bar in every officer's mess, and the pilots were encouraged to go on a binge every once in a while to relieve the tension.That brings to mind another thing - I don't know whether it had anything to do with tension or not - and that was a kind of negative fatalism that seemed to effect some people. Later on we had a sad thing happen at 213 Squadron. One day just before a patrol was scheduled to take off, one of the pilots who was going along, went up to the adjutant, who had come out onto the field, and gave him a little box with some trinkets and a letter and said, "Send these home to my mother will you?" The adjutant looked surprised and asked why. The pilot said, 'This is it, I don't think I'm coming back from this one. The adjutant tried to talk him out of his pessimism, but the man wouldn't be persuaded. He was killed on that patrol. Some people say that's a premonition. :I don't know, but it's bad psychology to start to take off with that feeling. I think that has something to do with it.

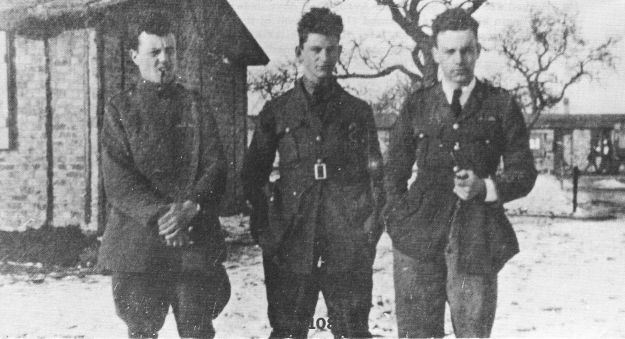

Above. From left: Lt. H. H. Gilbert, Lt. Huston, Lt. H. Fellows, Equipt. Officer,and Lt. A. B. Posevear. Stalhille, Belgium.

Below. From left: Lt. A. S. Chick, 2nd Lt. Sims, and 2nd Lt. Burton.

We could turn inside the Fokkers and were quicker. We'd put that wing right down and pull it around in a vertical turn, and they couldn't stay with us. Oh, they could loop and roll too. The first time I ever rolled a Camel I think it must have gone over three times before I righted the darn thing. After our initial instruction and solo in the Camel we built up our flying time to gain confidence in handling this sensitive craft in formation work and target practice.

At Eastchurch we had a target located just below the surface of the bay where we had our air to ground firing range. It looked something like a submerged submarine and was plainly visible to us when flying overhead. We would make firing passes at this target, diving down and lining it up in the sights, squeezing out short bursts, then pulling back and climbing up and around in a wide circle to come back down for another pas . The bu.llet splashes were clear evidence of how good or bad our marksmanship was. We repeated this procedure until we had expended all our ammunition and then returned to the field.

One morning I was scheduled to be on the range early and had flown out to the area. I was soon busy circling and diving, and doing pretty well, as I remember, when, as I was coming down for another run and had the target in my sights with my thumbs poised to press the triggers, splashes suddenly appeared in the water all around the target. I hadn't yet touched the triggers. I took a quick look around, and there practically on my tail and slightly above was 'another Camel I could now both see and hear his guns firing. For a fraction of a second I just; stared, incredulously, then abruptly swung the stick over and back, curving around and up in a climbing turn to get away from this intruder who seemed to be trying to use me as a target. I didn't hang around, but flew back to the field, considerably agitated. I came in and landed and as I cut my engine, the C. 0., who had witnessed the incident out over the bay, came running up and wanted to know if I knew who it was. I climbed down out of the cockpit as the other fellow came in to land. The C. O. collared him and gave him a real going over. It seems he hadn't been scheduled to be on the range at all that day, let alone at the time I was supposed to be on it. He didn't know the range was being used and didn't see me. Being below him I must have been in his blind spot as he dove, and his bullets were going right over my top wing. I recall one last thrill at Isle of Sheppey before leaving 204 T. D. S.. Three of us were up on a practice formation flight in Camels. An instructor leading the V, and another student and I slightly above and behind. I was on the right and the other student on the left. We had flown formation before, hut we were still far from being proficient

at it. Flying a straight course was one thing, but making turns in formation was something else. We had been flying sedately around for a while, managing fairly well, then the leader banked over into a rather sharp turn to the left. Following our instructions I pushed.ed on more throttle and pulled up in my turn to stay on the leader's high side as we started around. I had eyes only for the lead plane in this maneuver, trying to maintain the correct position in relation to it, and I didn't give a thought to the opposite wing man until a loud, roaring sound forced itself into my consciousness. At the same time I became aware of a dark shape sliding up at me from my left. I turned my head in time to see the underside of a plane's wing, two wheels and a whirring propeller about to chew into my top, left wing! I got a startled look at a pale, goggled face staring over the rim of a cockpit at me - and then the apparition was gone, dropping away in a steep side slip as fast as it had approached a moment before. The other wing man had had his troubles in that turn and we both had hung for an instant, a hair-breadth from touching and then, as suddenly, parted.

When I boarded the ship in New York to go to Halifax where we were to pick up our convoy, I had boarded the ship and then came back off to see my fiancee who was waiting outside the building. But they wouldn't let me out because I had seen the ship and knew' its name. She had a box of a hundred or so cigarettes for me that someone had given her, so she gave them to one of the men who was on his way in, to give to me. He had talked to my fiancee a little when she was arranging the transfer, and he told her that he didn't think he would survive the war. Later on the way across, he told me the same thing and sold a Canadian Bond at a discount to get cash to play poker because he didn't think he would be around after the war. He voiced this feeling to me several times during the trip overseas. Sure enough, he got over there and was flying a Pup or something, and was killed in a crash. If you feel that way about it and you takeoff with that attitude, it!s bound to affect everything you do. I think it has as much to do with your not coming back as anything. I never had the feeling that I wasn't coming back. Of course I knew there was a great risk and all, but it didn't worry me too much. I found that anticipation was the worst part. You take off, pick up your flight commander and start climbing toward the lines and until you get to where you can hear the anti-aircraft fire, or something begins to happen, you are apt to think about the chances of something bad happening to you. My experience was that when you actually got into combat, excitement displaced fear. Sometimes when we were gaining altitude approaching the lines, I would think the words of the Twenty Third Psalm. It was sort of reassuring to me to say it to myself. It gave me a good feeling about whatever might happen to me in the next few minutes ahead, it was in the hands of that Guy upstairs. But the minute I got into some action,the apprehensive thoughts disappeared and an my attention was on what was going on around me.

But I am digressing. To get back to our flight training at Isle of Sheppey - the attrition of students continued as the days went by. An Avro and a Pup were sent up with student pilots for mock combat practice. They flew around each other for a while, trying for favorable attacking positions." Then the fellow in the Pup thought he'd be smart and decided to loop around the Avro. He climbed above and behind the Avro, then dove under him, pulled back on the stick to begin his loop and zoomed right in front of the Avro pilot, who evidently didn't see him until it was too late. His propeller sliced right through the Pup's tail and took it clean off. The Pup nosed down immediately and dove straight into the ground, killing the pilot. The Avro, also damaged in the collision, crashed too, but luckily the,pilot wasn't killed. One day a Camel got into a spin right over the field and ploughed into the ground with such force that the engine had to be dug out. Of course there wasn't much left of the pilot in that one. Another time somebody pulled the wings off .a Camel in acrobatics. He was too rough on the controls I guess, or there was a weakness in the structure. That happened occasionally. It seems to me now, looking back, that learning to fly in that time of limited knowledge about the phenomenon of flight, in primitive and too often, unreliable equipment, that our days of flight training were a continuous series of close calls, narrow escapes from disaster, and for those who didn't survive, the ultimate and final tragedy of death The Camel was a very maneuverable airplane and was very quick on the controls. It could out-maneuver a Fokker, but couldn't out-climb or out-dive it.

One day a group of us students were talking and a South African pilot who was at Eastchurch wondered what would happen if he took a hen up to 4, 000 ft. and let it go. Somebody challenged him to do it. So he captured one of the hens that frequently wandered over from a nearby farm. He put it in a plane, took it up to 4, 000 ft. and threw it out. And the hen, flapping madly, came floating down squawking all the way, losing feathers as it frantically beat the air in an erratic course to the ground. It finally touched earth with a soft thump, turned over on its back, and recovering immediately, made off as fast as it could go, protesting loudly and apparently, except for its dignity, unharmed. Of course the C. O. knew nothing about this before hand. I think he saw the hen after it landed and wanted to know, "Who the hell did that

I finished flight training at Eastchurch on September previous June 24th, I had logged 75 -1/2 hours in Avros, 6 hours being solo time. On September 16th I was ordered to the School of Aerial Fighting at Marske-by- Sea in Yorkshire, but did no flying there. Five days later I entered Grove Military Hospital at Tooting Grove SW 17 for treatment of Scabies which I had somehow contracted. I remember a nurse there telling me that I was the only one in the ward whose case was mentionable. All the rest were in for var.ious forms of V. D. I languished at this institution for three weeks before getting a clearance for discharge and simultaneously orders to report forthwith to the Air Ministry, Strand, W. C. 2, London. There was to be no school of aerial fighting for me. I'd had one chance and that was all. Losses were heavy at the front and pilots were needed at the replacement centers. So to London and the Air Ministry where, with about thirty other training school products, I was about to receive my reward - designation as a reconnaissance, bomber or fighter pilot. We waited in a large room while the men were called into an inner office. My name, beginning with S, was way down near the end of the list. ,I had to sit there as the other fellows went in and then came out, saying, "I'm going to be a Bristol Fighter pilot.or, "It looks like I'm for R. E. 8s. " "--- bomber pilot." etc. Then it was my turn. Fighter Pilot - Camels! Only three of us out of that group were picked for Camel combat pilots. I was to be the lone survivor of that trio, the other two being killed before the end of hostilities A few days later I was issued orders to report to No. 5 Pilot's Pool at Wissant, France, near the Channel Coast opposite Dover. There was a regiment of Scottish troops in kilts aboard that boat that I took and when we got outside the Dover break- /water, the sea became very rough. I've never seen so many seasick men in my life. Some hours later when we arrived in France, they were a sorry looking bunch. But

they lined up on th~ dock just the same and marched off with rhythmic strides to the squeal of their bagpipes, just as if nothing untoward had happened. At Wissant+I flew only Camels, getting in cross country, aerial firing practice,

formation and some ferry flights. I remember I flew Camel No. 1526 from Walmer, England across the Channel to No. 210 Squadron located at Tetegham, near Dunkirk. Then on October 27th a call came in for three pilots to be sent to No. 213 Squadron at Bergues as replacements for three men lost in combat over the lines. Two other fellows and I were as signed as the replacements and were ordered to report to the squadron at once. We packed our kits and were ready when the squadron motor lorry arrived to take us back to Bergues. It was not a long journey, but it was after dark and raining when we pulled into the airfield. No lights were visible any-- where. The lorry,stopped in the darkness and the driver said, "Here we are, sir."

No. 213 Squadron, R. A. F., was formerly No. 13 Squadron, R. N. A. S., a Seaplane Defense Squadron before it reorganized and was equipped with Sopwith Camels. It moved to B'ergues in January 1918, and at that time it was commanded by Major Rona1d Graham, later to be Air Vice-Marshall, C. B.. C. B. E., D. S. O. ,D. S. C.. D. F. C., J. P. He died suddenly in 1967 just prior to a planned visit to this country.

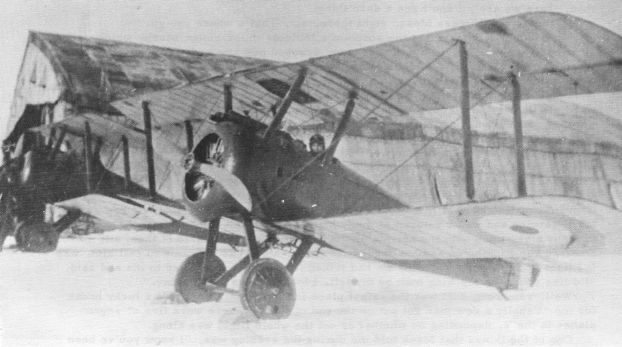

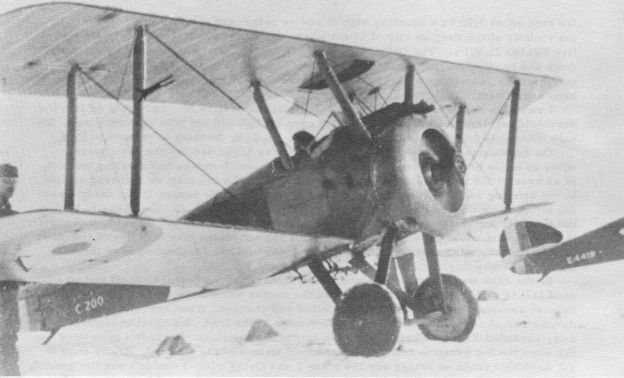

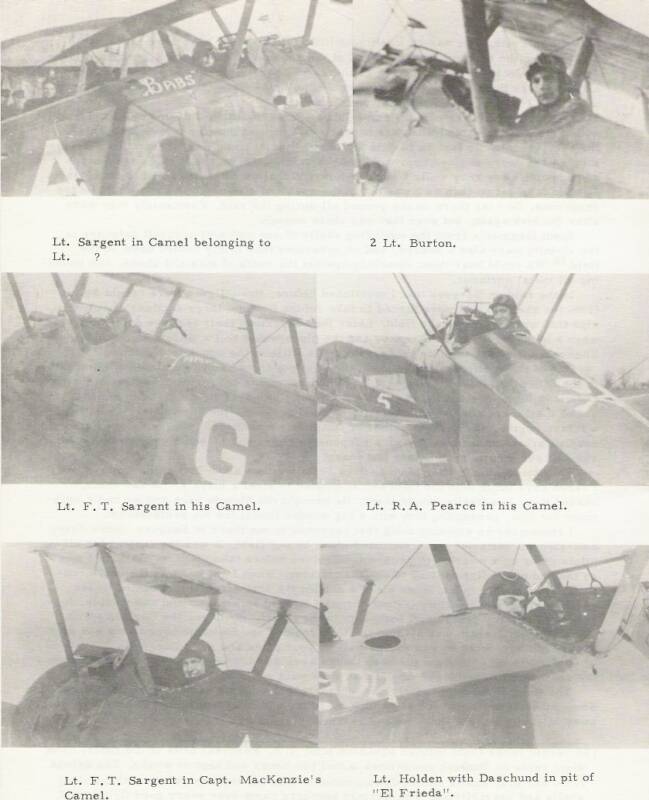

Above. Lt. F. T. Sargent in cockpit of F3l2l, C Flight, in which he got all his combat time.

Below. Lt. WaIter S. Phelps in front of C Flight hangar in Camel F85ll at Stalhille, Belgium.

I looked out trying to see something. It was black as pitch. I said, "What do you men, there we are!, I don't see a darn thing.!' "There's the Officers Mess, right there, sir. That's where you go.We could barely make out the shape of a building in the gloom nearby which was apparently it. We climbed out of the lorry, grabbed our kits and made our way to the long, low structure and fumbled around for a door to the place. Having located it, we went inside and found ourselves in a kind of hallway that was just as dark as it had been outside, but for a strip of light that came from a door ahead of us. Moving toward the light I tripped over something and dropped my bag with a thump. At that, the inner door opened and an officer stood in the lighted doorway peering out at us, then grinned. "You :must be the new replacements. Come on In. He opened the door wide and we filed into the room. Captain W. J. MacKenzie was his name and he invited us to sit down and have a drink with him. We removed our coats and relaxed in the informal atmosphere of the rather sparsely furnished room, and in a few minutes were engaged in conversation with Mackenzie, who gave us our first information of what life at an operational squadron would be like. He had seen a lot of service and was a veteran of many hours of over- the-lines flying. He had been in many a skirmish with the enemy, including the most formidable of them all, Baron Manfred von Richthofen and his Jagdeschwader 1. Mack, as we came to call him, was C Flight Commander, and after we had talked for a while, he turned to me and said, "I'd like you to be my wing man on my left. I lost my man there today" Well, you know, that was the safest place in the formation. It was a lucky break for me. Usually a new man got put on the end of the V. There were five or seven planes in the V, depending on whether or not the whole flight was along. One of the things that Mack told me during the evening was, ,"I know you've been through the Training Depot Squadron and they told you about the Immelmann turn. For God 's sake don't ever use the Immelmann turn! Youlll be a sitting duck! The minute you get up there and you lose flying speed, you fall off one way or the other, and that' s when the Heinie will pour it into you. Never, never do an Immelmann turn. That made a big impression on me and I never tried that maneuver in combat. Itr s a funny thing, but I remember almost nothing about my first familiarization flight at 213 which took place on October 29, 1918. Camel F3l2l was assigned to me and I kept it right on through the war's end. After that it doesn't show up in my log. I don't know what happened to it. My first contact with the enemy occurred on my next flight on October 30th. I must refer to my flight log as the details of that mission are also lost to' memory.

Capt. William. John MacKenzie from Port Robinson, Ontario, was formerly RNAS and had served with 209 Sq. He was in the famous air battle in which Richthofen was killed and was the only Allied casualty, suffering a painful flesh wound in the back. He was awarded the D. F. C. and Belgian Croix de Guerre.

No. 213 Squadron's opposition over the Flanders sector came mostly from Fokker D. VII's of the Marine Feld Jagdeschwader Flandern, under the command of Pour le Merite holder, Oblt. S. G. Sachsenberg, based at Neumunster and Coolkerke, Belgium.

Above.Mechanic running up Camel C200 of 213 Squadron. Stalhille, Belgium.

Below. Lt. F. T. Sargent in Capt. W. J. MacKenzie's lightning emblazoned Camel.

Walking around the wing of the Camel, he pointed to the fuselage under the cockpit and said, "Sir, did you know you still have all your bombs in the rack? Well, I darned near flipped.I was so absorbed in getting back to the field I had completely forgotten about everything else, including the bombs and the radio mast. I flushed and made some foolish remark about wanting to keep them for souvenirs. I knew our orders were to drop them in the Channel if, for any reason, we had to come back with them still aboard. A crash or a hard landing with the bombs in the rack could create a nasty

situation.

I was the only one to get back to our field that day. I don't think we lost anybody, but the rest of them landed all over France. The fellow who was leading me landed somewhere else, and Mackenzie and several others landed on the beach. Whenever that fog rolled in, it was thick! The next entry in my log was dated November 4. C Flight again had the morning high offensive patrol. This time we dropped down into a group of seven enemy Fokkers that we found cruising at 14, 000 feet. They turned immediately when they saw us coming and dived away east, too fast for us to catch.

That afternoon we were again heading out over the lines, climbing hard, with Mack leading. He suddenly waggled his wings to indicate the presence of enemy planes, so I began to look around and up above to try and spot them. Then I saw them, quite a few planes, high above us. Mack continued to climb fast and I was sticking right close to him when my engine began to falter. We had two Bosch magnetos in our Camels and, I switched off one and switched on the other - she still kicked. I put both on and she still kicked. I was unable to maintain my position in the formation and was

beginning to lag behind. We carried Very pistols in our planes with different color cartridges to fire in case of need. This day I think the color was red - we changed it often - and I fired off a red one to signal the others that I was leaving the patrol. Our orders were not to continue on if we had engine trouble, but were to head back and try to make it home safely. One plane with a malfunctioning engine could endanger the whole patrol. So I banked around and stuck my nose down, heading back for the lines and safety. I was at 15,000 or 16,000 feet, so had plenty of altitude to get me

back with my ailing engine. But I kept my head turning, scanning the sky just in case some unfriendlies caught sight of me all alone and entertained some thought of interfering with my plans to get back home. Then looking back, almost in the sun I saw a single plane, quite a way back, but diving toward me. I said to myself that's a Heinie and thinks I'm a lame duck. I kept looking around at the plane and it kept coming closer. I steepened my angle to pick up more speed, but he continued to gain on 'me. He was right on my tail, and I thought, I've got to do something! I pushed the nose down even more, and picking up considerable speed, I hoicked the nose right up and over. My opponent swept by under me and kept going down. When I saw that he was now below me, it gave me courage and I took after him as fast as my faltering

engine would pull me. I had my thumbs on both triggers, about to clamp down on them when, there through my sights I made out a red, yellow and black circle on an upper wing. It was the Belgian cockade. As realization dawned on me I moved my thumbs off the triggers and pulled to one side. He probably didn't even see me. It was close. I was all set to pour it into him. I eased off on the stick and continued on my way down at a more leisurely pace, now that the tension was gone and I was on our side of the lines. However, just to be safe, I decided to land at Varssenaire, a former

German airfield on the outskirts of Bruges, now in British hands, instead of trying for our field at Bergues. The mechanics soon had the trouble rectified and I took off for the 30 minute flight back to Bergues, arriving before the patrol had returned.

The log book entry for that experience, contained no hint of the tension and pressure faceg by the men who flew those primitive aircraft, each time they left the ground, even if they didn't get into combat. Under the remarks column was: 'Very heavy mists. Lost way. L. B. R. 1 (landed with bomb in rack)

For some reason, perhaps because of unfavorable weather conditions, Irecorded no flying time during the next two days. However, life went on at the squadron as usual and some of the things that happened in those days are just faint memories now, and others are just as clear as if they had happened a few years ago instead of fifty five.

Some of the pilots there were quite superstitious. Sims carried a rabbitl s foot as a talisman and wouldnrt think of taking off without it in the cockpit. MacKenzie had a feeling about matches and would leap out of his chair and come across a room to blow out a match if someone was trying to light a third cigarette on it. Lt. H. H. Gilbert wrote recently about a kind of "reverse" superstition:

IThe figure 13 stands out very prominently in my war service. So many people are superstitious about this figure because of the people involved in the Last Supper, 12 disciples and Jesus. However, 13 has always been a lucky number for me.

My first day in the army was 13 September and my first day in civvie life was the 13th of August. Before I went to the R. F. C. I was in the 5th Field Ambulance in France, picked up typhus (trench fever) at Ypres in 1916; invalided back to England. When I was better I was transferred, to the 13th Field Ambulance and returned to France on the 13th of August. I later rejoined the 5th Field Ambulance. At the Battle of Vimy Ridge there were 13 of us quartered in an old German dugout called U13, on the side of the main road leading up the ridge, under continuous fire by the Germans. We were picking up the wounded as they dropped on the road. None of our 13 were injured in any way. I think we were there for 13 days, but cannot swear to this particular 13. Then when I transferred to the R. F. C. I arrived in France with

the 213 Squadron..

Our location a few miles south of Dunkirk, caused us to suffer some anxious moments, uncomfortable hours in air raid shelters and lost sleep. The Germans must have considered the Channel port a priority target because they bombed it frequently. In fact Bergues itself was the target on at least one occasion a few months before I arrived there, and an unfortunate thing happened. Captain Paynter, a pilot who was about to be sent home on leave after a long period of service in France, heard the air raid siren go off. Instead of going to the shelter as he had been doing during the recent nearby raids, he was heard to say, The hell with it, I'm not getting out of bed again. They can bomb all they want, I'm tired of running to the shelter! So he stayed put and was killed. A bomb exploded not far from his quarters and splinters

came through the walls and struck him. The next day he would have been on his way back to home. He was the only fatality of that raid. Our Equipment Officer, Lt. H. Fellows was injured, as were several other men, a hangar was damaged with its planes, and latrines were blown flat by bomb blasts. Because of the casualties and damage caused by these raids, the sleeping quarters were moved to a farm location about 4 miles from the airfield. Consequently we had to be transported to and from the field each day by R.A. F. tenders or covered trucks.

Every squadron had its pets and mascots, mostly dogs I guess, and 213 had its share of canines of all shapes, sizes and ancestry. But we had one dog, I think. we called him Fritz, who was an intelligent little fellow. Held been down in the bomb shelter so often he knew that the sound of the engines of approaching German raid ers meant that he was supposed to go there. His ears were much keener than ours, and he could hear them coming before we could and he'd run for the shelter before any one else. That's how \we knew they were coming.

One night they were coming and I didn't get the warning. If d been asleep. I woke with a start and realised what was happening. I jumped out of my sack and came out the door, running as as I could for the shelter. I could hear the peculiar thrumming of the Jerry engines approaching at that point. Of course it was dark outside and I couldn't see very well. I stumbled over a shallow ditch and fell flat on my face. I didn't dare get up as I was out in the open and standing up to run would be too dangerous. So I lay there on the ground all during the raid. Fortunately they were after Dunkirk again, but even that was close enough. Spent fragments from the exploding shells of our own anti-aircraft defenses in the vicinity were also a hazard, and on occasions they fairly rained down on the field.I° We could hear them smacking against the roofs of huts and sheds, and bouncing off metal surfaces.

In the raid on Bergues that I mentioned before, two officers were caught away from the shelters and were forced to take refuge in some large sections of culvert pipe that were laying on the field. Later they described their feelings during the raid when a bomb would explode nearby and the pipes would roll a little with the blast. Then when the next one hit, they would roll a little in the opposite direction. One of these officers, a Cockney, was quite a comedian. Sometimes of an evening in the Officer's Mess after dinner, he would put on his act for us. He'd get a chair and sit in it and pretend he was flying a Camel - he never flew a plane in his life but he'd sit there and put on a terrific show of pushing stick and rudder, imitating a rotary engine, and doing all kinds of imaginary maneuvers. His parody of our deadly serious daily lives struck a responsive chord and helped supply an outlet for some of our innermost tensions and fears.

This same officer figured in an other little incident about that same time. Some French boys came onto the field and attempted to steal a bicycle. He saw them, chased them and finally caught them. He brought the bicycle back and we had a ceremony for him, presenting him with a big wooden medal for his achievement. I remember an amusing thing that happened to me there at Bergues. Some heavy anti-aircraft batteries were stationed close by our field. It was the custom for all pilots going on a mission to relieve themselves before take off. One morning I was on the end of the line waiting to use the latrines. When I got in I was the only occupant. Things were quiet, when all of a sudden the anti-aircraft gun behind us .let go! It literally scared the****out of me! I jumped straight up and ran outside, for getting to pull my pants up. I looked up in the air and could see the German plane there. Major Graham was also on the field looking up. He came over to, me and said, "Sarge old boy, what do you say we pull up your pants and get going. I stammered, "I forgot the darn things were down. I don't think 1'll ever forget the sensation I experienced when those guns went off. The German was apparently on a photographic mission as no bombs were dropped Some other squadron on the alert took off to try and intercept him, but I think he got away. Usually after a.photo reconnaissance mission like that, there would be a raid.in the vicinity that night or the next night after dark.

A recent letter from former squadron pilot A. B. Rosevear tells of the raids. The night raids on Dunkirk sometimes lasted two hours and kept us awake. The debris from our a. a. shells rained down around us and the sky was ablaze with bursting shells and searchlights. The German bombers came over every good flying night and raised hell on earth. all around us.

The atmosphere at our squadron was very informal, quite in contrast to the rather rigid discipline at the Training Depot Squadron back in England. Major Graham was a fine officer and gentleman, an awfully nice chap. He was like a father to us and we were all very fond of him. When we had a mission scheduled, we'd all gather in a room next to the mess where we held our briefings. Graham would usually be sitting on a soapbox and we pilots would be sitting or standing around him while he gave us details of the flight. If it looked like it would be a: rough one, ,he might say, "This is kind of a nasty mission. Good luck, men, good luck. Then the group would break up and file into the adjoining hallway where we kept our flying gear hanging on wall pegs, and climb into our Sidcots, fur lined boots, helmets and goggles, gloves, etc. then head out to the plane s.

Usually the planes that were to be flown on the mission were lined up in front of the hangar assigned to each flight. Each plane was served by a ground crew of three or four members; one man at the propeller to start the engine, one at each wing tip to restrain or guide the plane as it taxied, and one man at the rear of the fuselage to hold the tail down when the engine was revved up.

I'd usually give my plane a quick visual check as I approached, and walk slowly around it to the cockpit. If satisfied with its appearance, I'd stand beside the fuselage and make final adjustments to my bulky flight clothing before climbing aboard. When everything had been tightened, buttoned and buckled, I'd lift one booted foot into the recessed fuselage stirrup just aft of the lower wing, put one hand on the top of the fuselage and the other on the padded edge of the cockpit and heave myself up so I could- put my other foot on the wing root step. Then shifting my weight onto the left foot, I' d swing the foot that had been in the stirrup up along the fuselage side, over the rim and down into the cockpit, shifting my hands so as to grip both sides of the cockpit combing, supporting my weight on my palms and half sliding, half easing my self into the bucket seat down inside the confines of the open cockpit.

Once settled in the seat with the safety belt fastened securely, feet snugged up against the rudder bar, spade handled stick between my knees and the bare metal of the twin Vickers gun butts just in front of my face, there wasn't much room left for moving around. However, this restriction of space did have its compensations.- The proximity of the machine gun breeches allowed easy access for rectifying most of the stoppages that were apt to occur. Because the Camel' s cockpit was so far forward, we were practically sitting on top of the rotary engine and when we placed our feet on the rudder bar, they were right next to the heat of the whirling power plant with just. the fire wall in between. Some of the warmth seeped through and helped protect our toes, boot covered though they were, from the terrible numbing cold that we often suffered at higher altitudes that late in the year. This same position up front also gave us good visibility forward and down over the leading edge of the lower wing.

When everything inside the cockpit was checked and ready for the start-up, lid look out at the man standing expectantly by the propeller and give a nod of my head. He would immediately say, "Switch off, petrol on, suck in, Sir!" I'd repeat the words aloud after him, checking to make sure that the switch was off and the throttle open slightly. Thus assured, he'd. pull the prop through a few times, then setting himself and grasping the outer part of the blade with both hands, he'd call out, "Contact, Sir! As 1 called back, "Contact!" while snapping the switch to the ON position, he'd give the prop. a rhythmic but vigorous,'downward §wing and step back. Sometimes the Bentley would catch 'On the first try, and sometimes the sequence would have to be repeated, maybe several times, before "it would catch. hold with a throaty sound.sending a burst of bluish smoke swirling back from the exhaust ports.

After it had warmed up a bit and had settled into a continuous, smooth blend of detonations, I'd advance the throttle to a higher position and check it out on each magneto. Then, if the response was satisfactory, I'd open it up as far as it would go and let it bellow and shake for a few seconds. The men holding the wing tips and

tail section braced themselves against the straining aircraft during this check and then relaxed a little as I'd bring it back down to an idling setting and look over to where the C. O. was standing. Directing the take off, he would signal each man to move out in his turn. When he motioned me out Id wave a gloved hand at the wing men, watch them yank the chocks away from the wheels and then push the throttle forward. It needed a generous boost of power to start it rolling, but when it was moving well enough the men who were guiding it at either wing tip let go. I'd taxi out to the take off position, turn into the wind and push the throttle forward all the way. The rising tumult of sound that was unleashed by that simple movement of my hand would beat back at me through the thin partition at my feet and. in the swirling blasts of air hurled into the open cockpit by the force of the shimmering propeller just five feet from my goggled and whale oil smeared face. Gathering momentum, the plane would rumble and bounce along over the uneven turf, faster and faster, until finally I could lift it off with a gentle back pressure on the stick. Just as soon as we were off, the bumping and pounding would abruptly cease and I'd experience that peculiarly pleasant sensation of the transition from the solid, rough earth to the smooth, cushiony, almost sinuous quality of air sustaining flight.

Once free of the ground the Camel climbed at a pretty good angle, and I'd join the other planes of the flight climbing and circling, gradually pulling into our respective positions on the patrol leader's plane. After the flight had assembled to his satisfaction, the leader would turn and head for the lines, and if we were on a high offensive patrol, begin climbing in earnest. We usually flew a fairly tight formation, but if we got a little too close to the leader, he might look around at us and indicate that he didn't want us that close, and we'd slide out a little to allow a wider interval between planes. While we were gaining altitude on the way to our patrol area, we frequently had to make changes in our course, depending upon such things as wind, visibility, clouds, other aircraft in the vicinity, etc. Maneuvering a formation of fighter planes around in those days called for a certain amount of flying skill on the part of both the man leading the flight and the individual members, and even so simple an action as a change of direction, if botched up, could be a rather hairy experience. We were pretty well trained by the time we reached the front and we didn't suffer any accidents in our formations. Nor did I ever see any collisions in a fight with the enemy. The closest thing to a collision with a German that I knew of happened to a close friend of mine in A Flight before I joined the squadron, and that was the result of a deliberate attempt to ram.

Lt. A. Beatty Rosevear came to 213 Squadron around the first of September, and on the 28th of that month was involved in a mission attacking enemy ground troops and barracks. During the course of this low level assignment he experienced a number three stoppage in one gun. Since the other gun would still fire, he continued his strafing runs until he had exhausted the ammunition in that gun. When the last cartridge had been fired he broke away and climbed, heading back toward the lines alone. He hadn't gone far when he spotted two Fokker D. VI1 s behind and about 200 feet below him. Their dark color had blended well with the earth and they had managed to approach from that angle without his having seen them until now. Startled, Rosevear made a fast decision. He knew that the type of stoppage he had in his gun might be cleared by a sharp blow on the feed block with his Very pistol, but the result might also be a hopelessly broken feed block. In the same instant that he discarded that maneuver for lack of time, he pulled his Camel around in a tight turn and dove straight at the nearest of the approaching Fokkers on a collision course. Posevear made up his mind that what happened next would depend upon the enemy pilot, and his time for decision making was short. At the last instant the German banked aside and Rosevear flashed through the spot where the Fokker had been that instant before and pulled up in a climbing turn into the protection of a layer of clouds, losing sight of the enemy. A short time later he cautiously let down through the gray mists and broke into the clear again. The Fokkers were no where to be seen, but he found that he was over the boundary between Belgium and Holland, and the Dutch gunners were not long in letting him know that his presence was not welcome there. Staying away from neutral territory, he turned northwest and headed for the North Sea. When he crossed the coast he dropped down to a few feet above the surface of the water, following a course that would bring him back to Dunkirk and his nearby base at Bergues. The Germans seldom followed if one used this return route over the sea. When he landed at the airdrome he reported to operations and found that held already been listed as missing.

Getting back to the final week of the war, the next date in my log is November 7 I remember this day because of what happened near the tag end of it. We had been standing by all day, but the weather was bad and no patrols were able to get off. I did: record an afternoon "test flight" of 35 minutes, and this may have been a weather

flight to check conditions away from the immediate vicinity of the field. Apparently the report was unfavorable as my log shows no more air time, and I do recall that around 4:30 or 5 Of clock Major Graham said, Well, boys, flying is washed out for the day. Were all going to Dunkirk and have a grand old Binge. Well, we went down to Dunkirk and went to a big restaurant right on the quay there on the edge of the harbor. The whole squadron went in there to a private dining room that had been reserved for us and pretty soon the champagne was flowing all over the place. Things were going in grand style, when all of a sudden along about 10 0'clock the bells in

the town began to ring, whistles began to blow, and the head waiter burst into our room and announced in a near hysterical voice, "Gentlemen, la guerre fini!" We were up on the tables and under the tables whooping it up. I went out into the main dining room and was standing on the table leading them in song, when Major Graham came in and said we all had to go back to the squadron. Somewhat perplexed we stumbled out of the establishment, piled into our assorted vehicles and headed back,for Bergues, arriving there about midnight. The C. 0., looking very sober, told us to gather around him. "I'm sorry gentlemen. he said, "But the war is not over. That report was a false alarm and tomorrow were off again. " And sure enough, we were.

That next morning, November 8, a full complement of 18 planes left the ground .and assembled its three flights into formation before heading out on a Squadron High Offensive Patrol. We encountered a considerable amount of clouds along the way which restricted visibility and made formation flying difficult. After several hours or so of arduous wheeling around the murky skies over the nemy's territory we returned to our field having seen no visual evidence of his aircraft.

I was not scheduled for the afternoon trip, but Captain Mackenzie took eight other Camels with him on a swing around behind Ghent. About eight miles s. s. e. of the city their low flying formation was fired upon by a machine gun anti-aircraft emplacement and Mack led his charges down in a retaliatory attack on the hostile battery, giving them a good taste of their own medecine. The morning of November 9th found us again in the air over hostile territory on an offensive patrol, scouring the skies for enemy aircraft. About la miles east of Ghent we encountered a group of 4 lozenge camouflaged Fokkers who accepted our challenge of combat and engaged us in a brief but vicious fight that saw one E. A. go go down out of control. The fight broke off as suddenly as it had begun, and the sky was clear of enemy planes once again. We continued our patrol without further enemy sightings. Over Ghent we received moderate amounts of inaccurate anti-aircraft fire, and observed fires 'on the docks below. I took part in an afternoon patrol which was uneventful and I so noted it in my log with the abbreviated comment, N. T. R.

November l0th, the next to last day of hostilities, the squadron was alerted to take part in a secret mission, the details of which were to be with-held until the pilots had flown to the forward airdrome at Varssenaere to be refueled. After lahding there, we all gathered in a group around Major Graham, who was again leading the mission. Soon a dark green limousine drove onto the field, and when it pulled up near us, two men, one of them in the uniform of a Belgian general, stepped out. At this point Major Graham disclosed the details of the mission to us, saying that the squadron would be acting as a protective escort for the man in the generals uniform, who was actually the King of Belgium, and his aide, who wished to survey the front lines in that sector from the air. When we had been briefed on our assignment we dispersed to our planes, the King and his aide were bundled into flying suits, given helmet and goggles, and assisted into the observer's cockpits of two D. H. 4' s that were parked nearby. Then, with the gas tanks replenished, the whole group took off and 213 Squadron arrayed itself at various levels around the royal entourage and proceded on this rather unusual mission. With heads constantly turning and eyes continually searching the skies for signs of hostile aircraft, it wasn't surprising that presently someone spotted one, a low flying two seater nosing into the area of our protective responsibility. I was flying in my usual position off the left wing of Captain Mackenzie, C Flight commander. When Mack became aware of the presence of the German plane below us, he waggled his wings in the signal to attack and nosed over into a dive. Down I went sticking close to Mackenzie's wing. A Flight had also seen the enemy and was likewise diving to the

attack from a lower level, behind it's leader, Captain MacKay

In no time the four Camels that comprised A Flight that day had caught up with the Boche, which proved to be an L. V. G., and the startled pilot dove to near tree top level in an attempt to evade their attack. The flight broke formation and for a frenzied few minutes made individual close up firing passes at the zigzagging two seater. Having descended to such a low level they were unable to get below him and were forced to pull away in vulnerable climbing turns as they finished their run-ins. In doing so, they caught considerable punishment from some accurate shooting by the observer, who managed to hole most of them in spite of the erratic movements of his own aircraft.With the air around the L. V. G. filled with flying bullets, the eventual outcome was inevitable. First, the scrappy gunner was caught by a well placed burst and dropped out of sight inside the fuselage, his dangerous gun finally silenced. Then, under continuous pressure of the attacking Camel's, the enemy pilot tried to make a landing. The plane nosed down to a field, struck the ground, bounced and skidded along, and finally came to rest with its nose furrowed in the earth and its tail pointing to the sky.