Early in December 1918 three of us were assigned to ferry some Camels from Wissant, France back to Stalhille. A D. H. 9 was used to fly us over there. It seems to me that we all went at one time. I don't recall how exactly how we did it, but 1 do remember that plane was heavily loaded with the three of us somehow crammed into the rear cockpit. The flight over was all right, but when the pilot made his approach into Wissant and flared out to touch down, he didn't make enough allowance for all the extra weight and we hit the ground hard - bang! The landing wires parted, we bounced and he gave full throttle to go around again. We staggered

along andmanaged to remain aged to remain airborne while he made a wide circle and came in for another try

all three of us hanging on for dear life, hoping he'd make it this time. Fortunately he judged it right the second time in and we landed all right, but when we came to a stop, the wings were drooping.

On one occasion all the flying officers went up to Brussels on pas s. I think we put up at the Americana Hotel. We had all gone down to the bar about 5 O'clock in the evening, and who should be there but the Prince of Wales. He was wearing the R. A. F. blue uniform with wings, and when he saw us come in, in our assortment of R. N. A. S. , R. F. C. and R. A. F. dress, but all with wings, he set the whole squadron up for drinks. We accepted his generous offer with pleasure, and while we stood at the bar with glasses in hand, he talked pleasantly with us for a few minutes, then politely excused himself and left. We thought he seemed quite shy.

Our Squadron Gunnery Officer was a Captain Maine, a man much older than the rest of the officers. I guess he must have been in his fifties at least. Sometimes when we didn't have any duties that required our attention, we took walks together. He often confided that he thought some of the pilots in the squadron were rather a crude lot. They knew how he felt about them and wanted to play a trick on him. One time when a D. H. 9 was visiting the field, they persuaded him to go up for a ride. He was supplied with flying gear, helped into the rear seat and securely fastened in. The pilot, who had been primed for his role before hand, climbed into the cockpit and the engine was started. As the plane trundled out to the end of the field and swung around into its take off run without even stopping, the assembled pilots pounded each other on the back in gleeful anticipation. Within minutes they were howling in delight at the way the 9 was being flung around the sky over the field. For a two seater pilot this man knew just what he could do with his heavy craft, and, for some minutes, he skirted with the limits of its capabilities, but always maintained his mastery over it by his skillful handling, giving poor Captain Maine a wild one for his first ride. Needless to say, the occupant of the rear seat got "educated" in those few moments, and the watcher s on the ground got their satisfaction. The chastened Gunnery Officer, now fully appreciative of what flying was. "really like", was returned to earth and never complained about the pilots again.

Remember the Dachshund, Fritz, I told you about at Bregues? Well with things a little more relaxed after the fighting had stopped, Lt. Sims used to bundle him into his cockpit and take him up on some of our practice missions. The little dog seemed to enjoy these rides in the drafty Camel and never got airsick. That reminds me of another ride one of our pilots gave to some feathered creatures that did not have a happy ending. One of the boys went to England on leave, and when he was due to return, he decided he I d bring a 'special treat back to the squadron in the form of a couple of crated turkeys that he'd bring back in the plane he was ferrying. Unfortunately, that old nemesis, the Channel fog was to write finish to his good intentions and his life, so that neither he nor the turkeys ever showed up at Stalhille. On the first leg of his return flight, the gray oblivion that spread from the chilly waters to the countryside, inland from the French coast, effectively concealed the outlines of a low hill that lay in his path as he let down dangerously low in an attempt to get his bearing s. He flew smack into its unyielding hulk before he had a chance to react to its sudden appearance out of the heavy mists in front of him. He was a nice fellow. Too bad to have survived the war and then have that happen.

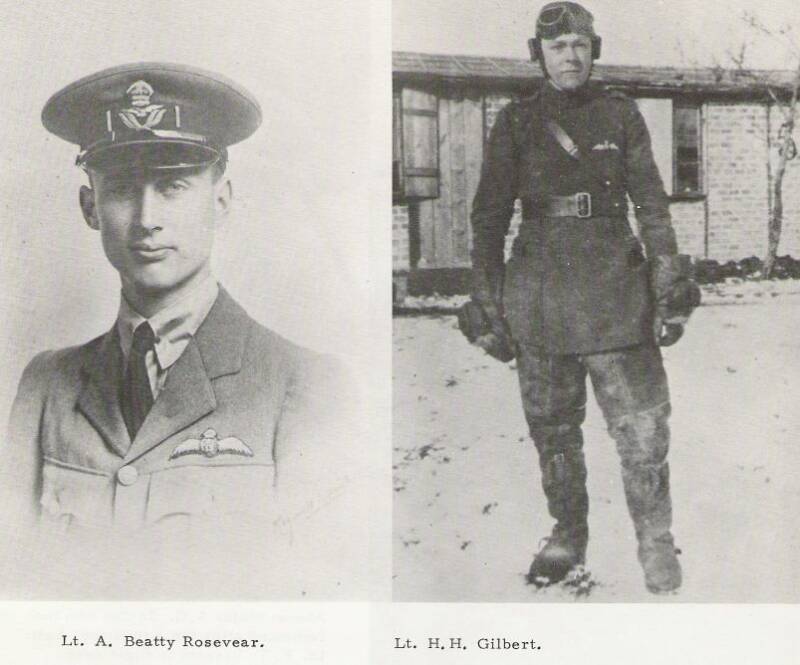

Back in October, before I had joined the squadron, another American pilot, Lt.Kenneth MacLeish, who, like Lt. David Ingalls, was on "loan" to 213, was lost on a patrol along with Lt. Jack Green, one of the regular Flight Commanders. He was reported as shot down and missing, and no further word had been heard of him. On December 30th, in a renewed attempt to uncover some hint of his fate, several of our planes piloted by Capt. McKay, Lts. Gilbert, Hancocks, Rosevear, Garner and Turner, took part in a sweep of the area where he was thought to have gone down. Lt. H. H. Gilbert was one of the pilots who saw the wreckage of his Camel close to an old building in the flooded area near Penvyse. Thus the mystery of his disappearance was solved and his body was finally recovered

According to Stewart K. Taylor Lt. MacLeish was lost on the 14th of October and was flying Camel D9673. This was his first flight over the lines.

.

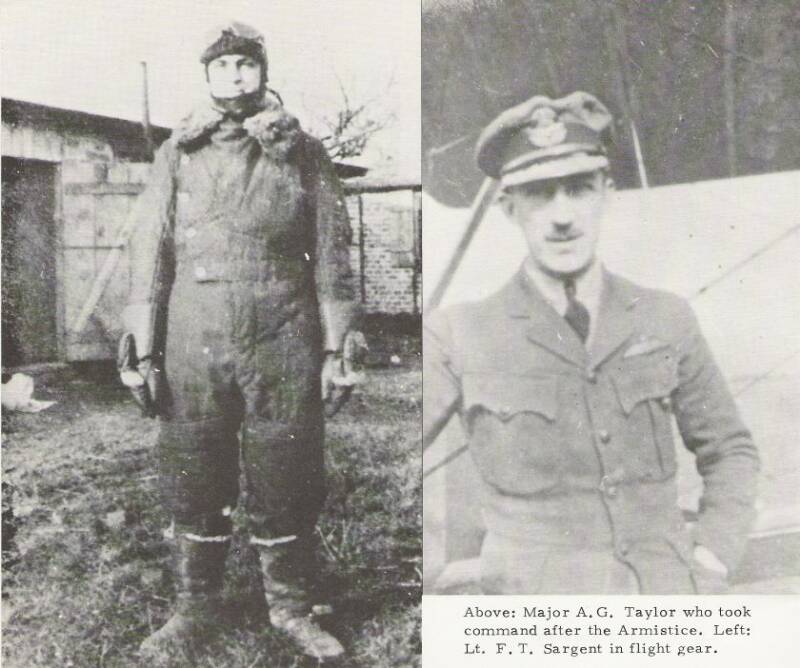

After the new year in 1919 we had a change in command and Major Ronald Graham, our popular C 0., was transferred to another assignment, being replaced by Major A. G. Taylor, an officer with no combat flying experience, formerly C. O. at my old flight school, 204 Training Depot Squadron.

In January we made flights along the coast, down as far as Boulogne and Calais, putting in time and keeping ourselves fit, for even at that stage we didn't really know whether or not the Armistice was to be a permanent end to hostilities.

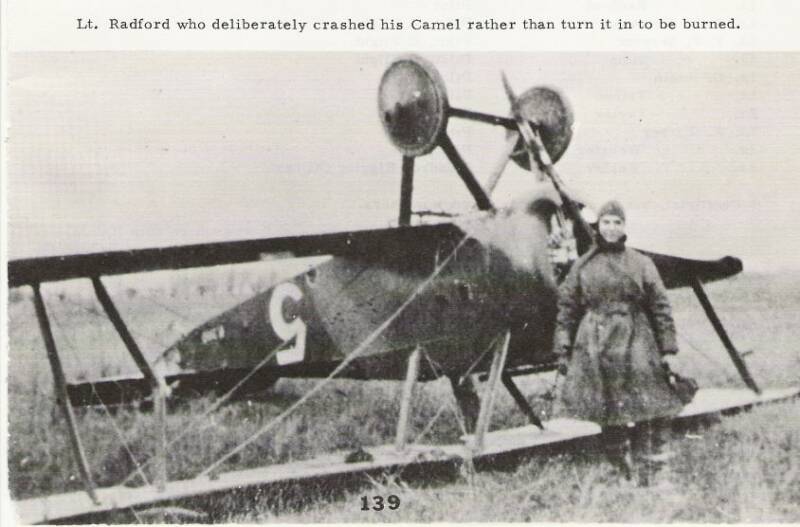

A group of us went up to have a look at the former German Naval base at Zeebruge with its famous mole, which had been the target of many attacks in the past involving 213 pilots. We were impressed with this huge facility curving out into the sea and took snapshots of the bomb damage to the concrete structures and the huge gantry cranes there. When we ferried the last of the squadron planes to No. 11 Aircraft Park at Ghisteile on February 25 to turn them in, we were allowed to take something from them to keep as a souvenir. I got the mechanics to remove the propeller of the Camel I had flown there that day. It was F3099 and had been built by Clayton and Shuttleworth Ltd. of Lincoln, England. I had the blade cut up so I could carry it with me

and kept the two tips and the hub. Later I had a clock put in the center of the hub section for use as a mantel decorafion. The tips had some kind of fabric covering to protect them from moisture. What I really would like to have had was the shrapnel-cracked windshield from my combat Camel F3l2l that was removed after that hair-raising episode with Archie the day before the war ended. I really should have gotten that.Lt. Gilbert kept the spade -handled joystick from his plane, with the two trigger levers and the blip switch for cutting the ignition. I don!t know what Lt. Rosevear kept from the plane he turned in, but I'll tell you about something else he got as a souvenir from another plane. When Beatty (Rosevear) first reported to 213 Squadron around the first of September, Lt. David Ingalls was on temporary duty with the squadron and he took Beatty out on his first trip over the lines several days later - just the two of them. They were approaching the lines when a noise like all the devils in hell let loose suddenly came from Beatty's engine, just under his nose, scaring him half to death. Despite his fright he had the sense to throttle back and at the same time he fired his guns to get Ingalls' attention. The sound of firing so close scared Ingalls, who thought he'd spotted enermy fighters. He jerked his head around and Beatty pointed to his disabled engine. Ingalls nodded in acknowledgement and escorted him back to the airdrome where Beatty managed to land ok. A broken rocker arm on one of the cylinders was

the cause of all the noise. Later the cylinder was sent to him by Sergeant Wilson,the engine man, and for many years after the war it was used as a gong to call people to meals at his summer home in Canada. .

.

After we had turned in all our planes, we stayed at Stalhille for a while, then were sent to a collecting encampment at Setques, near St. Omer, France. From there on April 9, Vimy Ridge Day, we were sent across the Channel to England and to barracks at Sandgate. Here, after a seemingly interminable stay, during which we fiddled away our time, getting bored and mad at the delay, wangling as much leave as we could in London, we at long last were issued orders to return to Canada. I think our port of embarkation was Liverpool, and there, with hundreds of other R. A. F. officers, we boarded the S. S. Megantic and departed the shores of "dear old Blighty" Once and for all.

The war was indeed over.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

With sincere thanks to those who offered their kind as sistance in the preparation of this article in the form of personal experience narrative, photographs, photocopying, data, names, facts, encouragement, editing, etc. among whom are:

Dr. H. H. Gilbert, A. B. Rosevear, Q. C., Russell Manning, Iver U. Penttinen, Charles Woolley, W. A. B. Douglas and R. V. Dodds of the Office Of The Directorate Of History, Department Of National Defence, Ottawa, Ontario, Stewart K. Taylor, and Fred T. Sargent.

The long plume of smoke from the puffing locomotive gave it away as it headed east across the Belgian countryside, loaded with troops. Graham took immediate advantage of this unexpected opportunity and signaled the squadron to go into the attack. The Camels fanned out and swung around into a large circle and in follow the leader style, began diving down at the train as it chugged along the rails. They came right down over the top of it and using the leading edge of their lower wings as a reference, the pilots would judge the proper instant for release and yank the bomb toggle in the cockpit, loosing the bombs. Plane after plane made its pass over the serpentine line of this on-rushing target, but it wasn't until Lt. Sims came in low, right over the locomotive, that spectacular results were achieved. Bomb bursts erupted on either side, and then, 'as Sims flashed over it and into a climb, the locomotive itself exploded in a huge ball of smoke, steam and flying debris. Sims later claimed that a bomb went right down the stack. Major Graham, who was flying low, along side at that moment, corroborated his opinion, and thatf s how it went into the report. The force of the explosion toppled the engine onto its side and as' it went, it pulled the troop filled cars over with it, bringing the whole thing to a shattering, grinding halt. German soldiers began jumping and crawling from the overturned and jack-knifed cars, running in all directions, seeking cover from the circling planes which were now diving and firing their machine guns into the wreckage. Some of the soldiers began to fire their rifles at them as they circled overhead. One pilot recalled seeing a white horse in a nearby field running in frantic circles, obviously terrified

at all the noise and fireworks.

About this mission H. H. Gilbert writes, "1 was in the same, low bombing raid when Sims dropped the 20 lb. Cooper bomb down the stack. I didn't see him do it, but I know the train stopped abruptly. It was my first bombing raid, so I paid most of my attention to flying my machine and getting back safely. Where did my bombs hit? I don't know.

Cont:-

Roster Of Officers* (Unofficial, but identified by surviving members).

Bergues, France and Stalhille, Belgium

Major Ronald Graham C. O. until after the Armistice

Major A. G. Taylor Replaced Major Graham as C.O. at Stalhille

Capt. A. J. Spellings Squadron Adjutant and Recording Officer

Capt. G. C. McKay A Flight Commander.

Capt. J. R. Swanston B Flight Commander. Killed in plane crash, India.

Capt. W. G. MacKenzie C Flight Commander

Capt. Maine Squadron Gunnery Officer

Lt. Burton Pilot

Lt. A. S. Chick Pilot, A Flight

Lt. Coombs Pilot, C Flight

Lt. H. Fellows Squadron Equipment Officer

Lt. G. C. Garner Pilot, A Flight

Lt. H. H. Gilbert Pilot, A Flight

Lt. M. N. Hancocks Pilot

Lt. Hodson Pilot

Lt. Holden Pilot

Lt. E. R. Huston Pilot

Lt. R. A. Pearce Pilot

Lt. W. Phelps Pilot

Lt. Pownall Pilot

Lt. Radford Pilot

Lt. A. B. Rosevear Pilot, A Flight

Lt. F. T. Sargent Pilot C Flight

Lt. Sims Pilot C Flight

Lt. C. Smith Pilot

Lt. Talbot Pilot

Lt. Taylor Pilot

Lt. A. Turner Pilot

Lt. Webste Pilot

Lt. Wesley Squadron Rigging Officer

A. B. Rosevear explained in a letter that Major Taylor had a difficult time as he came to us after the Armistice with no war flying, and having been trained in the RFG had difficulty with naval terms such as "steward" instead of "orderly","shipr s office" for orderly room", "number of Camels on deck" instead of "number of Camels in service". He tried to change some of these terms, but that didn't succeed, nor did it add to his popularity.